At the time of this writing in mid 2014, ECMAScript 6 — which practically in people’s minds means “the next version of JavaScript” — has not been officially released yet and support for its features is inconsistent across different environments. This comes as no surprise as things are still in the works. However, a lot of the features that will be available to developers when the upcoming version finally is released already have a lot of discussion surrounding them. One of these is that there is finally *finally* going to be an implementation of classes introduced into the JavaScript language.

It’s hard not to get excited about the notion of true classes in JavaScript, especially because of what it means for inheritance. We have looked at inheritance in JavaScript previously and how you can kind of mimic class-like behavior by using function objects as constructors and setting the prototypes of inheriting objects to instances of parent objects. However, with classes we will (hopefully), no longer have to worry about this.

Picking up the commonly-used-in-other-languages example of inheritance using animals, let’s see how things might look in ECMAScript 6…

class Animal {

constructor(){

this.color = 'brown';

this.size = 'medium';

this.age = 1;

}

sound() {

console.log('Grunt');

}

move() {

console.log('Running');

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

constructor(color, size, age) {

this.color = color;

this.size = size;

this.age = age;

}

sound() {

console.log('Woof');

}

}

var d = new Dog('Black', 'medium', 5);

console.log(d.size); // medium

d.sound(); // Woof

d.move(); // Running

So as we can see, the inheriting object will inherit items it does not specifically set for itself from the animal object. We can even take this a step further and inherit from Dog. If our constructor formed similarly compares to the object we are inheriting from, we can use the “super” keyword…

class Pomeranian extends Dog{

constructor(color, size, age) {

super(color, size, age)

}

sound() {

console.log('Yap');

}

}

var p = new Pomeranian('Brown', 'small', 5);

p.sound(); // Yap

p.move(); // Running

How sweet is that? With support for classes it appears that ECMAScript 6 is going to bring about much better implementations of inheritance that follow a more recognizable classical pattern like those seen in Java, PHP, and other languages. It’s something that those who program in JavaScript have been wanting for quite some time.

As mentioned earlier, current support for ECMAScript 6 varies across different environments. One place that you can experiment with some of the new features is this ES6 Fiddle. Classes are just one of the new features on the horizon, but there are other snippets of example code showcasing what else is new in ECMAScript 6 that you can explore,

When the web moved from HTML4 to HTML5, the rise of AJAX based web applications came along with it. AJAX (which stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) can mean a number of things but in practice it often refers primarily to the client/server interaction where JavaScript can be used to communicate with a server by making calls at various times under various conditions to send and receive data. This can be happening as often as you like in real-time without the user having to navigate to another webpage or refresh their browser (i.e. asynchronously).

What is an example of this? Well, say I wanted to put a stock ticker on my webpage or in my web application. I could use JavaScript to make a call to a service like some stock-market API that will give me quotes on a particular stock, get the data back, and display it in the UI in a visually appealing manner. As these market prices update over time, I can periodically update the quotes that I’m displaying on the page. The format that the server returns data in really depends on the service you are calling. It can often be be XML (as the X in AJAX suggests) but another popular format is JSON. I actually like JSON a bit better, myself. The experience of parsing through everything in code just seems a bit cleaner so if there is the option to have the data you are trying to get returned to you in JSON, I’ll usually opt for that.

Because JavaScript is such a universally cross-platform language capable of running on so many different devices in different environments, this can be a great way for different applications to communicate with each other. The result, hopefully, is to give your users the best experience possible whether they are on desktop, mobile, tablet, or some other crazy device.

In the early part of the 21st century, something else that was and has been absolutely ubiquitous across the internet is WordPress. From it’s humble beginnings of being exclusively web-based blog software, it has transformed into essentially the most popular content management system (CMS) used for running small and medium sized websites or web applications.

In what follows, we can look at how we can undertake merging these 2 things together. We’re basically going to look at how we can send and receive JSON data to a WordPress database and read from and write to the tables within WordPress using AJAX.

Read More »

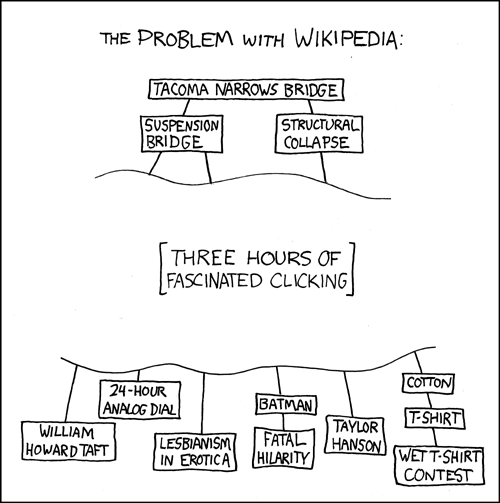

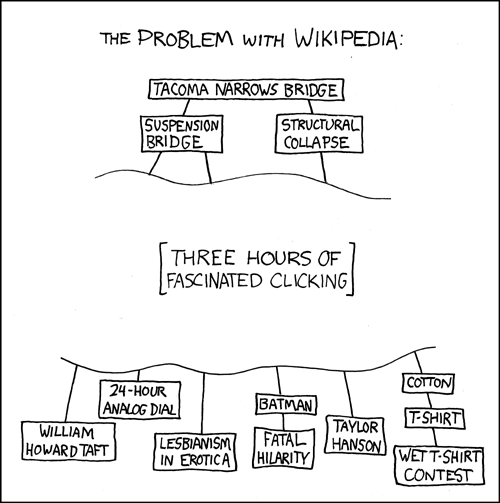

Where would we be without Wikipedia? It’s hard to believe how we survived without this icon of the Internet. A novel idea of being an encyclopedia that anyone can edit, it’s always kinda interesting how you can look up an article about one thing and then end up somewhere completely different as you jump from article to article by clicking through its link-heavy content. But more important than that, Wikipedia is the authoritative mediating source of arbitration in all Internet arguments where the combatants usually don’t have anything other than extremely biased and inflammatory blogs as source material at hand and are too lazy to do their own research using actual respectable academic sources.

I’ve even heard that this spills over into the “real world.” Wikipedia has reported that it sees a huge spike in traffic coming in on mobile devices on Friday and Saturday nights and the underlying cause of this is believed to be attempts to settle disagreements than break out from drunken arguments in bars.

So, all things considered Wikipedia usually has a good base on information just about any subject under the sun. And it got me thinking that a lot of websites and applications could benefit greatly from having an easy way to pull data from Wikipedia and use it to populate content. Fortunately, Wikipedia is built on some software that does provide an API for doing this. I remember seeing the super-slick Google Chrome experiment 100,000 stars put out by the folks at Google used Wikipedia excerpts as a brief description of each star. So I thought I’d look into the process of pulling data from Wikipedia using JavaScript and write it down because I figure someone else would find it useful at some point. Because other wikis are built upon the same foundation as Wikipedia, itself, this is not limited to getting data from Wikipedia alone. You can query other Wikis as well.

Read More »

Sometimes it is important to get information about the current URL using JavaScript… whether it be the current location, weather a certain query string parameter exists, or just about anything else. It is often the case that you need to know this information on the client-side in your webpage or application.

You could definitely write a bunch of different functions to handle this, but since getting or setting URL-related stuff in JavaScript shares a common area of functionality, it’s probably better to group them all together. For this it is reccomended that we use something like the JavaScript modules approach discussed here. That way we can group everything together.

So below is a starter module called urlInformation. Everything is namespaced to that variable…

var urlInformation = (function () {

var urlContains = function (pathArray) {

for (var i = 0; i < pathArray.length; i++) {

if (window.location.href.indexOf(pathArray[i]) === -1 && window.location.href.indexOf(pathArray[i].toLowerCase()) === -1) {

return false;

}

}

// did we reach the end? everything passed

return true;

};

var hasParameter = function (name) {

// Get query string

fullQString = window.location.search.substring(1);

paramCount = 0;

queryStringComplete = "?";

if (fullQString.length > 0) {

// Split string

paramArray = fullQString.split("&");

//Loop through params, check if parameter exists.

for (i = 0; i < paramArray.length; i++) {

currentParameter = paramArray[i].split("=");

if (currentParameter[0] == name) //Parameter already exists in current url

{

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

};

var getParameter = function (name) {

var match = RegExp('[?&]' + name + '=([^&]*)').exec(window.location.search);

return match && decodeURIComponent(match[1].replace(/\+/g, ' '));

};

return {

getParameter: getParameter,

hasParameter: hasParameter,

urlContains: urlContains

};

})();

As we can see here, we have some methods (psuedomethods really) on this mobile that we can call directly anywhere in our code like so…

urlInformation.getParameter('id');

This will return the value of the “id” parameter that is appended to the query string in the URL ?type=something&id=7.

What’s great about this approach is that we can easily add any methods we want, using any variables we want, and as long as we add it to the return object we are in good shape. For example, we could expand our mobile below and add a hash function that gets the current value of the #hash in the URL…

var urlInformation = (function () {

var urlContains = function (pathArray) {

for (var i = 0; i < pathArray.length; i++) {

if (window.location.href.indexOf(pathArray[i]) === -1 && window.location.href.indexOf(pathArray[i].toLowerCase()) === -1) {

return false;

}

}

// did we reach the end? everything passed

return true;

};

var hasParameter = function (name) {

// Get query string

fullQString = window.location.search.substring(1);

paramCount = 0;

queryStringComplete = "?";

if (fullQString.length > 0) {

// Split string

paramArray = fullQString.split("&");

//Loop through params, check if parameter exists.

for (i = 0; i < paramArray.length; i++) {

currentParameter = paramArray[i].split("=");

if (currentParameter[0] == name) //Parameter already exists in current url

{

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

};

var getParameter = function (name) {

var match = RegExp('[?&]' + name + '=([^&]*)').exec(window.location.search);

return match && decodeURIComponent(match[1].replace(/\+/g, ' '));

};

var getHash = function () {

return window.location.hash;

};

return {

getParameter: getParameter,

hasParameter: hasParameter,

urlContains: urlContains,

getHash: getHash

};

})();

And then we can call it like so..

urlInformation.getHash();

to get the current hash in the URL.

As JavaScript continues to evolve, a long time mainstay of JavaScript, arguments.callee, is going by the wayside. Depending on the time you are reading this, it may have already. arguments.callee was/is a way for JavaScript developers to have a function call itself when there might be some cases when the name of the function is not known or it’s an unnamed anonymous function. As is stated in the Mozilla Developer Network article…

callee is a property of the arguments object. It can be used to refer to the currently executing function inside the function body of that function. This is useful when the name of the function is unknown, such as within a function expression with no name (also called “anonymous functions”).

John Resig, know for his involvement with the jQuery project, used it in earlier versions his discussion/example on a pattern of JavaScript inheritance.

/* Simple JavaScript Inheritance

* By John Resig http://ejohn.org/

* MIT Licensed.

*/

// Inspired by base2 and Prototype

(function(){

var initializing = false, fnTest = /xyz/.test(function(){xyz;}) ? /\b_super\b/ : /.*/;

// The base Class implementation (does nothing)

this.Class = function(){};

// Create a new Class that inherits from this class

Class.extend = function(prop) {

var _super = this.prototype;

// Instantiate a base class (but only create the instance,

// don't run the init constructor)

initializing = true;

var prototype = new this();

initializing = false;

// Copy the properties over onto the new prototype

for (var name in prop) {

// Check if we're overwriting an existing function

prototype[name] = typeof prop[name] == "function" &&

typeof _super[name] == "function" && fnTest.test(prop[name]) ?

(function(name, fn){

return function() {

var tmp = this._super;

// Add a new ._super() method that is the same method

// but on the super-class

this._super = _super[name];

// The method only need to be bound temporarily, so we

// remove it when we're done executing

var ret = fn.apply(this, arguments);

this._super = tmp;

return ret;

};

})(name, prop[name]) :

prop[name];

}

// The dummy class constructor

function Class() {

// All construction is actually done in the init method

if ( !initializing && this.init )

this.init.apply(this, arguments);

}

// Populate our constructed prototype object

Class.prototype = prototype;

// Enforce the constructor to be what we expect

Class.prototype.constructor = Class;

// And make this class extendable

Class.extend = arguments.callee;

return Class;

};

})();

This pattern of adding an “extend” property to an object, is recognizable in other JavaScript projects such as Backbone.js.

Class.extend = arguments.callee;

With arguments.callee being deprecated, What can we do to replace it? The solution can be found in named function expressions. Without going into too much detail about what they are, in the code above. We can change this part…

Class.extend = function(prop) {

...

}

to the following…

Class.extend = function extender(prop) {

...

}

Then instead of using arcuments.callee at the bottom we can use…

Class.extend = extender;

By using a named function expression, we have replaced arguments.callee. In doing this we can modernize our applications and sentimentally waive goodbye to relics of the past.